Restoring the Sundarbans is a matter of national survival

When negotiators convened in Brazil for COP30 to chart the future of the world’s forests, Bangladesh didn’t need a reminder of what’s at stake. Along our southwest coast, climate change is not a forecast—it is a daily constraint on water, work, and safety. The Sundarbans is the last natural barrier between millions of people and the accelerating hazards of a warming ocean.

Global attention may have centred on the Amazon, but the parallel for Bangladesh is unmistakable: the fate of our defining forest and the fate of our people are entwined, and our buffer for mistakes is perilously thin.

The mangrove shield under pressure

In the coastal delta, resilience isn’t jargon—it’s survival. Salty water has seeped into ponds once used for drinking. Rice paddies show crusted white scars where crops struggled and failed. Cyclone alerts arrive in relentless succession, leaving families with little time to rebuild before the next storm. In this precarious geography, mangroves do more than anchor sediment; they slow deadly water, soften wind, nurture fisheries, and provide fuelwood, honey, and income.

They also provide something less quantifiable: confidence. People sleep easier knowing a forest stands between them and a storm’s full force. But that confidence is eroding.

Sea levels are rising and tidal surges are pushing salt farther inland, degrading soils and freshwater. Traditional rice varieties falter. Fish spawning seasons and habitats are disrupted, reducing catches. Many men migrate for work, while women shoulder expanded responsibilities—managing households, tending animals, securing water and fuel, and coaxing food from stressed land. Their labour and expertise keep communities afloat, yet they remain underrepresented in planning and decision-making.

Human-induced damage compounds the crisis

Unregulated shrimp aquaculture converts wetlands and weakens embankments. Illegal logging and vessel pollution chip away at ecological integrity. With diminished freshwater flows from upstream, natural regeneration slows. The losses don’t always come as a headline-grabbing collapse; they accumulate, season by season, until the safety net thins.

Science underscores what residents already know: mangroves can substantially reduce storm surge heights. During cyclones like Sidr, Aila, Amphan, and Remal, the Sundarbans blunted impacts that might otherwise have been catastrophic. Every strip of mangrove lost weakens that defence—and every hectare restored strengthens it.

A forest that defines a nation

Spanning roughly 10,200 square kilometres across more than a hundred islands, the Sundarbans is a living mosaic of channels, mudflats, and trees that support hundreds of fish species, migratory birds, and the Bengal tiger. Much has been lost since the mid-20th century due to clearing, conversion, and encroachment. With seas rising and salinity intensifying, scientists warn that without rapid course correction, parts of the mangrove could vanish within decades. That would not only be an ecological tragedy—it would unravel livelihoods, displace communities, and amplify disaster risks far beyond the forest’s edge.

Policy exists; implementation lags

Bangladesh has recognised the stakes on paper. Strategies such as the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 and the National Adaptation Plan place mangrove recovery at the heart of climate resilience. Yet delivery on the ground is uneven. Some restoration sites disregard local hydrology and sediment flows. Field offices lack staff and equipment. Conflicts over land—especially where commercial aquaculture is expanding—undermine conservation. Community participation, particularly women’s leadership, is too often treated as optional rather than essential.

Financing nature with fairness

COP30 reinforced a crucial principle: forests are not peripheral to climate solutions; they are foundational. Concrete and embankments alone cannot secure a sinking, storm-battered delta. Momentum is growing for nature-based solutions, including ecosystem restoration and blue carbon initiatives that could mobilise funds for mangroves. For Bangladesh, this is a real opening—if designed with safeguards. Financing must be transparent. Benefits must flow to local people. Conservation cannot justify dispossession.

The meeting also underscored the global interdependence of forests. Large-scale damage to major biomes like the Amazon can reverberate through climate systems, influencing rainfall and storm behaviour across oceans. What happens in distant forests ultimately shapes risks along the Bay of Bengal.

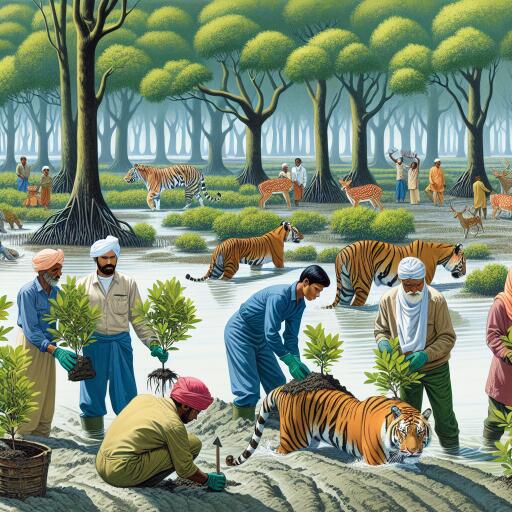

Restoration starts with people, not saplings

Replanting alone won’t save the Sundarbans. Success depends on reviving the water and sediment dynamics that build and sustain mangrove habitat, while empowering the communities who live with and steward these ecosystems.

Priorities include:

- Hydrology-first restoration that matches species to salinity and sediment realities.

- Guaranteeing freshwater pulses where feasible to support regeneration.

- Zoning and regulating aquaculture to prevent further encroachment and embankment damage.

- Stronger controls on vessel traffic and pollution within sensitive channels.

- Equitable benefit-sharing, with accessible finance for community groups and women-led enterprises tied to sustainable livelihoods like honey, fisheries, and mangrove-compatible agriculture.

- Independent monitoring and community oversight to keep projects accountable.

A narrow window to act

The Sundarbans stabilises coastlines, buffers cyclones, underpins fisheries, and anchors regional identity. As the mangroves thin, displacement grows and vulnerability deepens. For a nation on the front line of climate impacts, restoring this forest is not a symbolic gesture—it is a national safety strategy.

If we move with urgency, align finance with fairness, and centre local knowledge, the Sundarbans can continue to absorb shock and buy time in an era of rising seas and stronger storms. If we delay or cut corners, no wall we build will match what a healthy mangrove can do.

Protecting the Sundarbans means protecting Bangladesh—its people, its future, and its capacity to endure.

Leave a Reply