Ecogeomorphic Feedbacks Shape Louisiana’s Coastal Wetlands

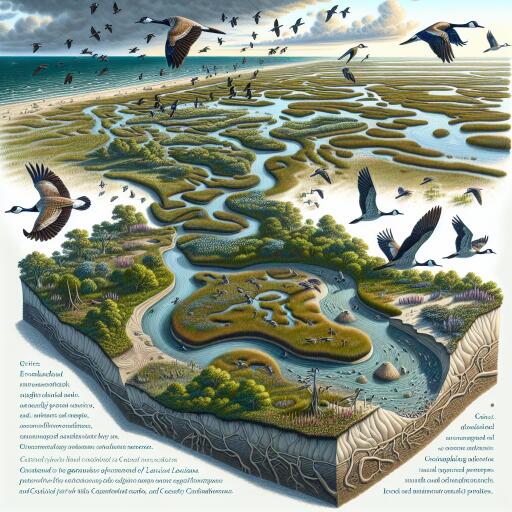

As seas rise and storms intensify, the fate of Louisiana’s coastal marshes hinges on a quiet but powerful set of forces: the two-way dance between living plants and shifting landforms. New research from a multidisciplinary team reveals how subtle feedbacks among vegetation, sediments, and water movement control whether these wetlands gain height or slip beneath the tide—especially in places where daily tides are tiny.

The engine behind elevation change

In microtidal marshes—where tidal ranges are often less than two meters—nature cannot rely on strong tidal currents to deliver the sediments needed to build land. Instead, the marsh builds itself. Plants slow the flow of water, trap suspended particles, and pack soils with roots and organic matter. In turn, as the ground surface rises, it changes how water moves across the marsh, which feeds back into how much sediment can be captured and how plants grow. These looping interactions, known as ecogeomorphic feedbacks, can either amplify elevation gains or accelerate losses, depending on local conditions.

Plants as landscape engineers

The study highlights how foundational marsh species do far more than simply occupy space. Dense stands of grasses and sedges baffle waves and currents, encouraging mineral sediment to settle out. Beneath the surface, roots weave through the mud, adding volume and strength; even as some roots decay, the organic material that remains helps maintain soil structure. Together, these biological processes supplement the physical supply of sediment—an essential function where tidal energy is low and subsidence is ongoing.

A patchwork of resilience and risk

Elevation change in these wetlands is not uniform. Small differences in microtopography, soil texture, and connectivity to channels create a mosaic of responses. Slightly higher patches, for instance, may support vigorous plant growth and steady accretion, while lower-lying depressions that stay flooded longer can experience weaker plant productivity and diminished sediment trapping. This fine-scale variability means that broad-brush assessments often miss where the system is most at risk—or where it is most capable of self-repair.

Human fingerprints on natural feedbacks

Levees, canals, and other infrastructure alter freshwater and sediment delivery, reshaping the baseline conditions that ecogeomorphic feedbacks depend on. When river inputs are diverted or flow paths are simplified, opportunities for sediment deposition can decline. Reduced sediment availability and altered flooding patterns can erode the very feedbacks that help marshes keep pace with rising seas. Recognizing these constraints is crucial to designing interventions that work with, rather than against, the system’s natural dynamics.

Looking forward with long-term data and models

By blending years of precise elevation measurements with process-based models, the research projects how marsh surfaces might evolve under various climate and sea-level scenarios. The results point to two divergent futures. In places where biological and physical processes remain tightly coupled—strong plant growth, steady sediment trapping, robust soil building—marsh elevation can keep up, at least for a time. Elsewhere, feedbacks weaken, and the system drifts toward thresholds where losses accelerate. Once those tipping points are crossed, recovery becomes increasingly difficult without major changes to sediment supply or hydrology.

Guiding smarter restoration

These findings provide a roadmap for targeted action. Rather than spreading resources thinly, managers can focus on areas where positive feedbacks can be sparked or strengthened. Key steps include:

- Protecting and restoring vegetation communities that excel at trapping sediment and building organic soils.

- Reconnecting wetlands to freshwater and sediment sources, where feasible, to sustain natural accretion.

- Avoiding or redesigning hydrologic modifications that prolong harmful inundation or starve marshes of sediment.

- Using high-resolution mapping to identify microtopographic features that influence local resilience.

- Monitoring elevation and plant performance over time to catch early warning signs of approaching thresholds.

Lessons with global reach

While this work centers on Louisiana, the principles apply widely. Many coastal wetlands around the world experience limited tidal energy, rapid sea-level rise, or land subsidence. In these settings, the balance between plant-driven soil formation and available sediment will likely determine which landscapes persist. The conceptual and analytical tools developed here can help coastal regions elsewhere diagnose vulnerabilities and craft nature-based responses.

An integrated lens on a self-organizing system

Wetlands are quintessential self-organizing landscapes. Understanding them demands a synthesis of ecology, geomorphology, hydrodynamics, and climate science. By uniting detailed field observations with advanced modeling, the research disentangles the relative weight of roots versus minerals, plant growth versus inundation, and local topography versus regional sea-level trends. This integration moves wetland science beyond description into prediction—precisely what coastal planners need as conditions shift rapidly.

The bottom line

Coastal Louisiana’s marshes are not passive victims of sea-level rise; they are dynamic builders of their own terrain. But their success depends on the integrity of the feedbacks that link living plants to the soil beneath and the waters around them. Support those feedbacks—through smart hydrologic reconnections, strategic vegetation management, and vigilant monitoring—and wetlands can continue to buffer coasts, harbor wildlife, and store carbon. Undermine them, and the landscape can tumble toward collapse. In the tight margins of microtidal coasts, that difference is the measure of resilience itself.

Leave a Reply