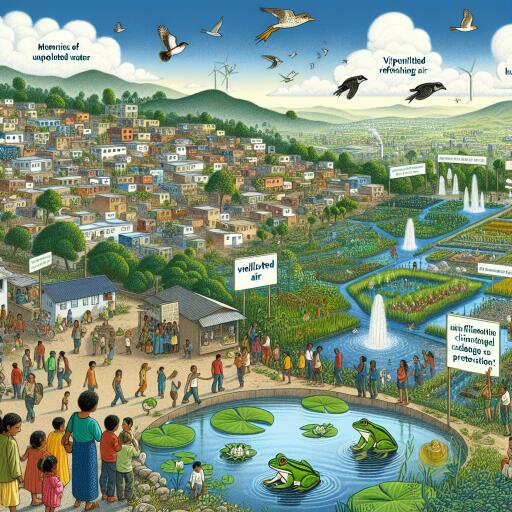

How memories of clean water, frogs and fresh air could help save Rio’s favelas from future climate disaster

In Rio de Janeiro’s hillside and lowland settlements, climate adaptation is being shaped not only by data and infrastructure, but by memory. Residents recall streams that once ran clear, trees that kept courtyards cool, and the chorus of frogs at dusk—everyday details that hint at ecological functions now lost. A community-driven effort across 10 favelas has been gathering these recollections through conversation circles with more than four hundred people of all ages, transforming lived experience into a roadmap for resilience.

The power of remembering nature

For many long-time residents, the soundscape of their childhood—frogs calling after summer rains, birds sheltering in shade trees—marked a time when local ecosystems buffered heat and floods. Now, faster runoff, concrete expansion and polluted waterways have diminished those natural defenses. By tracing where springs surfaced, where breezes funneled between homes, and where shade once fell in the late afternoon, communities are identifying precise places to reintroduce cooling vegetation, manage stormwater, and reconnect people with their environment.

This memory work is not nostalgia; it is spatial intelligence. Stories locate old creek beds now buried beneath alleys, or mango trees that moderated temperatures on schoolyards before they were cut down. Such details help residents and planners imagine feasible, low-cost interventions—small wetlands where water historically pooled, pocket forests where soil remains deep, and vine-covered pergolas along sun-baked footpaths.

Why the climate crisis hits harder in informal settlements

Across the world, and in Rio’s favelas in particular, the climate emergency compounds existing inequities. Overcrowding, informal construction, and limited access to sanitation and health services increase exposure to extreme heat, landslides, and flooding. Many communities also navigate the stress of territorial violence and uneven public investment, which undermines preparedness and recovery.

Heatwaves intensify the “urban heat island” effect where concrete and tin roofs trap warmth well into the night. Downpours turn narrow lanes into torrents, with drains clogged by uncollected waste. On steep slopes, saturated soils can fail; in low-lying areas like parts of Acari, water has nowhere to go. Pollution—from traffic, industry, or inadequate sewage—exacerbates respiratory and waterborne disease risks during climate extremes.

Turning memories into practical solutions

The conversations taking place across these 10 favelas do more than document loss; they drive action. Residents are translating memory into a portfolio of community-scale solutions:

- Cooling and shade: Planting native trees along pedestrian routes, building trellises for climbing plants, and creating “shade corridors” by aligning canopy cover between homes.

- Heat-proofing homes: Reflective roof coatings, rooftop gardens, and ventilation retrofits that channel prevailing breezes remembered by older residents.

- Water stewardship: Rainwater harvesting, cisterns, and small retention basins placed where water historically gathered, reducing flood peaks and providing supply during shortages.

- Stream and spring revival: Daylighting short reaches of buried creeks, installing biofilters and riparian vegetation to clean runoff, and marking historic spring sites for protection.

- Landslide risk reduction: Slope reforestation with deep-rooted species, terracing, and community-maintained drainage lines that keep hillsides stable during storms.

- Early warning and mutual aid: Neighbor-led monitoring of rainfall and runoff, coordinated alerts via messaging groups, and pre-staged materials to clear drains before downpours.

- Waste management as climate defense: Organized cleanups and simple waste traps in critical gullies that prevent blockages and reduce flood damage.

Mapping workshops—where elders draw vanished watercourses and youths log GPS points—are helping produce community risk maps. These maps guide where to plant, where to open space for water to spread safely, and which homes need priority support. The approach is iterative: test an intervention, observe how the neighborhood responds in the next storm or heatwave, then refine.

Memory as a pathway to climate justice

Documenting local ecological knowledge rebalances who gets to define risk and design solutions. For residents too often portrayed only as vulnerable, memory-based planning affirms a long record of environmental care: informal shade gardens that cooled courtyards, collective efforts to keep channels clear, and water-sharing during dry spells.

This is climate justice in practice. When communities articulate their own environmental histories, it strengthens the case for equitable investment—tree nurseries, safe public spaces, green infrastructure—tailored to local conditions. It also holds authorities to account: residents can point to precise, historically functional sites where a tree, a drain, or a pocket park would make a measurable difference.

Lessons for cities everywhere

The method emerging in Rio’s favelas is both simple and profound: listen first, map what people remember, and act where nature once worked with the built environment. Because interventions are small, distributed, and community-managed, they are relatively inexpensive and quick to implement. They also generate co-benefits—cleaner air, cooler classrooms, safer walkways, and renewed biodiversity, from pollinators to those once-familiar frogs.

Importantly, the process builds leadership among youth and women, who often coordinate caregiving and neighborhood networks. By anchoring adaptation in shared stories, it transforms climate action from a technical fix into a cultural project—one that restores pride, strengthens social ties, and reduces risk at the same time.

From memories to a safer future

The echoes of clean water and evening frog song are more than wistful recollections; they are blueprints. In the face of intensifying heat and storms, Rio’s favelas are proving that the most effective resilience can begin with a circle of neighbors, a hand-drawn map, and the invitation to remember. With fair support and sustained attention, those memories can guide practical changes—cooler streets, revived streams, sturdier slopes—that make the difference between disaster and recovery. Saving these neighborhoods from the next climate shock may start by listening to what they have already learned from the land.

Leave a Reply