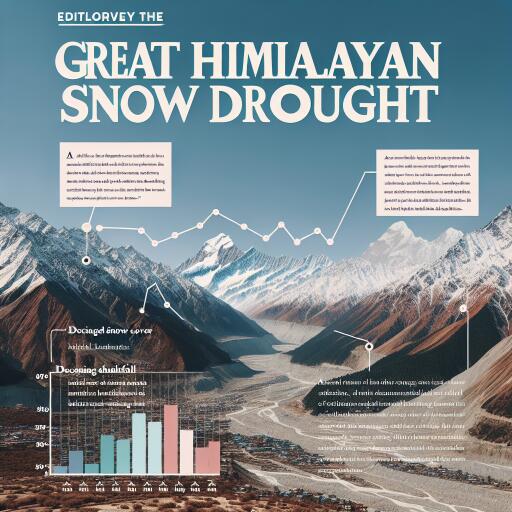

UPSC Editorial Analysis: The Great Himalayan Snow Drought

The Himalayas, long celebrated as Asia’s vast water tower, are experiencing an unprecedented “snow drought” — a season of abnormally low snow accumulation and unusually warm conditions. This is not just a weather anomaly; it is a structural warning for the subcontinent’s water security, food systems, energy planning, ecosystems, and regional stability. For aspirants of public policy and governance, this is a critical case of how climate variability intersects with geography, economy, ecology, and geopolitics.

What is a Snow Drought?

A snow drought occurs when the snowpack — the seasonal reservoir stored as snow — is significantly below normal. It can arise from reduced snowfall, warmer temperatures that shift precipitation from snow to rain, or faster-than-usual melting. In the Himalayas, where snow feeds glaciers and sustains river flows through the lean summer months, a thin snowpack disrupts the entire hydrological clock of the region.

The “Perfect Storm” Behind the Crisis

- Warmer baseline: Rising average temperatures lift the freezing level, turning potential snow into rain and accelerating melt.

- Altered storm tracks: Weakened or displaced western disturbances reduce the intensity and frequency of winter storms that traditionally bring snow.

- Large-scale climate modes: Events like El Niño can tweak atmospheric circulation, suppressing Himalayan snowfall.

- Aerosols and black carbon: Soot deposition darkens snow, lowering reflectivity and hastening melt; air-quality shifts also influence cloud formation and precipitation.

- Jet stream dynamics: A more wavy jet stream can divert moisture-laden systems away from the mountains.

- Land-use changes: Deforestation and development in mountain catchments alter local microclimates and water runoff patterns.

Economic Reverberations

- Agriculture: Reduced winter cold and thin snowpack cut soil moisture recharge, harming rabi crops in the plains and disrupting chill-hour requirements for orchards in hill states. Farmers face higher irrigation costs and greater yield uncertainty.

- Hydropower: Snow acts as a slow-release reservoir; diminished snowpack reduces predictability of spring and summer inflows, complicating grid management and revenue planning for run-of-river and storage projects.

- Groundwater and canals: Lower spring melt weakens canal supplies and slows aquifer recharge, pushing communities toward deeper, costlier groundwater extraction.

- Tourism and livelihoods: Skiing, winter trekking, and snow-dependent tourism suffer, affecting local economies and seasonal jobs.

- Risk and insurance: Heightened climate variability raises credit risk for mountain agriculture and infrastructure, pressing the need for tailored insurance products and contingency financing.

Environmental and Ecological Stakes

Often called the “Third Pole,” the Himalayas store the largest volume of ice outside the Arctic and Antarctic. A snow drought has cascading effects:

- Glacier mass balance weakens as reduced snowfall undercuts annual accumulation, accelerating long-term retreat.

- Rain-on-snow events raise flood and avalanche risks, particularly where rapid melting follows warm, wet storms.

- Rivers face altered timing of flows, stressing aquatic ecosystems adapted to seasonal pulses.

- Permafrost and slope stability degrade, increasing landslide hazards and threatening high-altitude infrastructure.

- Dry forests and grasslands become more fire-prone, endangering biodiversity and releasing stored carbon.

Geopolitical and Strategic Dimensions

Major transboundary rivers — the Indus, Ganga, and Brahmaputra systems — are intimately linked to Himalayan snow and ice. Variability in snowpack and melt affects treaty-era water-sharing assumptions, complicates hydropower coordination, and raises stakes for downstream flood management and delta sustainability. Urban water security in the plains and strategic logistics on high-altitude frontiers are both sensitive to these hydrological shifts. Enhanced data sharing, joint monitoring, and basin-level planning across borders will be central to reducing tensions and managing shared risks.

Way Forward: From Crisis Response to Climate Resilience

- Measure and monitor

- Expand high-altitude observatories, snow telemetry networks, and remote sensing assimilation to track snow water equivalent in near real-time.

- Develop sub-seasonal to seasonal forecasts tailored for hydropower, irrigation, and disaster management.

- Manage water differently

- Recalibrate reservoir operations for altered flow timing; integrate flexible hydropower and pumped storage.

- Invest in managed aquifer recharge, spring rejuvenation, watershed restoration, and demand-side efficiency.

- Climate-smart agriculture and horticulture

- Shift to varieties with lower chill requirements; adopt micro-irrigation, mulching, and precision advisories.

- Strengthen weather-indexed insurance and climate services for farmers and orchardists.

- Protect mountain ecosystems

- Conserve upper catchments, restore native forests, and regulate high-altitude construction to stabilize slopes.

- Cut black carbon and dust through clean cooking, improved diesel standards, and better brick kiln technologies.

- Reduce disaster risk

- Scale flood forecasting, avalanche early warning, and glacial lake monitoring; enforce land-use zoning in hazard-prone areas.

- Design climate-resilient roads, bridges, and power lines for a thawing, unstable cryosphere.

- Cooperate across borders

- Institutionalize snow and glacier data sharing, joint research, and basin-wide scenario planning.

- Align investments with risk-informed standards across the Indus, Ganga, and Brahmaputra basins.

- Mitigation alongside adaptation

- Accelerate clean energy, urban air-quality improvements, and land-based carbon sinks to slow warming and reduce soot deposition.

Conclusion

The Himalayan snow drought is not an isolated bad season; it is a signal that the water logic of South Asia is shifting. Responding effectively demands science-led governance, resilient infrastructure, diversified livelihoods, and regional cooperation. In other words, a definitive break from business as usual. The sooner policy, planning, and public investment align with this alpine reality, the better the odds of safeguarding lives, economies, and ecosystems downstream.

Leave a Reply