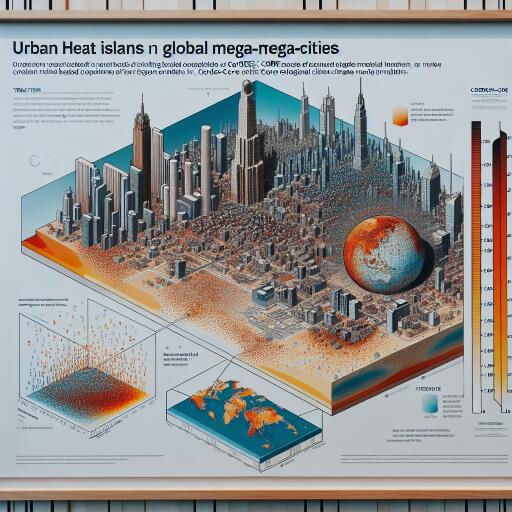

Representation of global mega-cities and their urban heat island in CORDEX-CORE regional climate model simulations – npj Urban Sustainability

From sweltering nights to record-breaking heatwaves, cities are on the frontline of climate change. Yet, capturing the complex dance between urban form, land surfaces, and regional climate remains a major scientific challenge—especially when aiming for global consistency across dozens of mega-cities. Recent modeling work explores how well two widely used regional climate models simulate urban areas and their heat signatures, offering a candid look at what today’s tools can and cannot do.

What was assessed

Two regional climate models from the CORDEX-CORE initiative—REMO and RegCM—were evaluated for their ability to represent cities worldwide. The focus fell on two components that are essential for urban climate analysis:

- How urban land-surface characteristics are described, especially the fraction of impervious surfaces such as asphalt and concrete.

- How the urban heat island (UHI) effect is reproduced, with particular attention to daytime versus nighttime behavior.

Despite operating at a relatively coarse grid spacing of approximately 25 kilometers, which cannot resolve neighborhood-scale variability, both models were tasked with identifying the broad urban fingerprint of the world’s largest metropolitan regions.

Main takeaways

- Even at coarse resolution, both models detect the thermal imprint of large urban areas on regional climate. The signal is strongest for mega-cities with expansive built-up zones that influence the land–atmosphere exchange over many kilometers.

- RegCM, which includes a single-layer urban canopy scheme, captures the nocturnal UHI more convincingly. This structure allows for a better representation of how building geometry and urban materials store heat by day and release it at night.

- REMO, using a simpler bulk urban parameterization, tends to dampen the nighttime heat island signal. As a result, nocturnal warming relative to surrounding rural areas is underestimated.

- Across both models, impervious surface area is systematically underestimated. This bias varies by region, creating geographic imbalances in urban land representation that translate into inaccuracies in local climate signals.

Why it matters

Urban heat islands shape energy demand, air quality, public health risks, and the equity dimensions of exposure during heat events. If models understate impervious surfaces or downplay nighttime heat retention, they can underestimate the severity of heat stress and fail to capture how urban design choices—like tree cover or reflective materials—modulate local climates. These biases complicate efforts to evaluate adaptation strategies, from cool roofs to urban greening, at scales relevant for policy.

The resolution challenge—and the data gap

A 25-kilometer grid cannot resolve the diversity of street canyons, parks, waterways, and high-rise districts that define city microclimates. Under such constraints, the quality of urban land-use data becomes decisive. When impervious fractions are too low or outdated, the simulated energy balance tilts toward cooler, more evaporative conditions than reality. That misrepresentation is then amplified in heat metrics—particularly at night, when stored heat is released from urban materials.

The study underscores the need for refined, harmonized urban land-use inputs that reflect rapid urban growth, informal settlements, and intra-urban heterogeneity. Incorporating recent satellite-derived products and dynamic updates can substantially improve how models “see” cities.

How to improve projections for cities

Advancing urban climate modeling within regional frameworks will require two complementary steps:

- Enhanced urban parameterizations: Move toward more detailed canopy schemes that capture building geometry, materials, shading, ventilation within street canyons, anthropogenic heat emissions, and the role of vegetation and water features.

- Better urban land-use data: Integrate high-resolution, up-to-date maps of built-up areas, surface materials, green and blue infrastructure, and evolving urban footprints, especially in rapidly growing regions.

Coupling these improvements with robust evaluation using observations—from urban heat networks to remote sensing—will help close gaps in nighttime UHI, extreme heat representation, and seasonal contrasts.

Implications for planners and adaptation

Even with current limitations, the models provide useful signals about where and when urban heat intensifies under regional climate influences. For mega-cities, this can guide heat action plans, energy system planning, and urban design strategies that prioritize cooling at night—when health risks often peak. As parameterizations and datasets improve, regional climate simulations can become a more reliable backbone for assessing interventions such as tree canopy expansion, reflective surfaces, permeable pavements, and water-sensitive urban design.

Bottom line

Large cities leave a detectable mark on regional climate that today’s regional models can capture, but the strength and timing of the urban heat island—especially at night—depend heavily on how urban surfaces are represented. RegCM’s more explicit urban canopy scheme better reproduces nocturnal UHI, while REMO’s simpler approach tends to mute it. Across the board, underestimation of impervious surfaces remains a key source of bias. The path forward is clear: pair improved urban physics with sharper urban land-use data to deliver credible, city-relevant climate projections.

Leave a Reply