Modeling river and urban related microplastic pollution off the southern United States – npj Emerging Contaminants

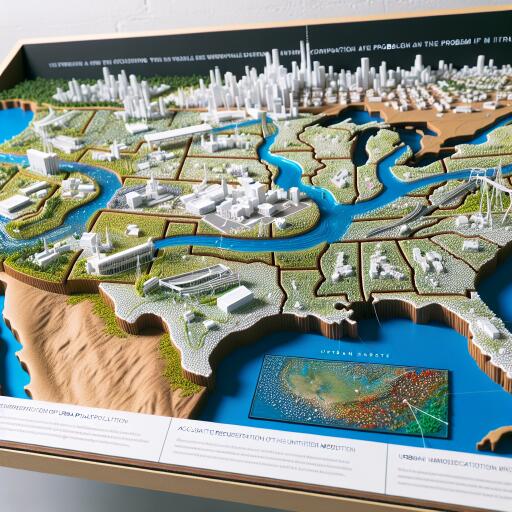

How do tiny plastic fragments travel once they leave cities and rivers along the U.S. Gulf Coast? A high‑resolution ocean model paired with a particle‑tracking system sheds new light on that question, revealing where microplastics accumulate, how seasons and currents steer them, and which protected areas and species face the greatest exposure. The analysis focuses on the northern Gulf of Mexico and represents two main sources: river plumes dominated by the Mississippi–Atchafalaya system and outfalls from wastewater treatment plants serving large metropolitan areas along Texas, Louisiana–Mississippi–Alabama, and Florida’s west coast. The findings carry important implications for coastal management and conservation planning.

How the ocean and particles were simulated

A submesoscale‑resolving ocean circulation model (about 1 km grid spacing) was coupled to a Lagrangian tracker to follow virtual microplastic particles for 30 days after release. Particles covered a range of sizes and densities to capture sinking, floating, and neutrally buoyant behavior, and tests also included the effect of wave‑driven Stokes drift. River and urban sources were weighted differently to reflect contrasting discharge volumes and input rates. Results are reported for particles that settle to the seabed versus those that remain in the water column.

Where settled microplastics build up

Urban outfalls create highly localized seabed accumulation near release points, with three clear coastal clusters: along the Texas shelf, immediately east of the Mississippi River delta, and along Florida’s west coast. When realistic sinking is included, the footprint tightens and most material settles quickly near outfalls. Without strong settling, the footprint broadens alongshore.

Rivers contribute far more settled microplastic than urban outfalls, driven by the magnitude of the Mississippi–Atchafalaya discharge. Nearshore concentrations ramp up toward the coast, and the bird‑foot delta emerges as a dominant hotspot. Under weak settling, a broad, diffuse band spreads along much of the northern Gulf shoreline; with stronger sinking, settling becomes patchy but extremely concentrated near river mouths.

Suspended microplastics: who stays aloft and where they go

Particles that remain in the water column after 30 days show different behavior. Urban‑sourced microplastics again cluster close to their sources, mirroring the settled pattern. River‑sourced microplastics disperse widely, with the highest concentrations near the Mississippi delta and a pronounced westward extension along the Texas shelf. Scenarios that allow rapid sinking leave fewer particles suspended; when sinking is weak or absent, substantially more plastic remains aloft.

Winds, the Loop Current, and eddies shape the map

Regional circulation governs the large‑scale pattern. Prevailing winds blow from east to west most of the year, weakening in early summer. Surface currents respond accordingly, driving westward transport and focusing river‑borne microplastics along the Texas shelf—one of the Gulf’s major hotspots. East of the delta, transport is generally limited, except during summer lulls and when clockwise eddies or intrusions of the Loop Current pull coastal waters offshore. On the west side of the delta, particles are more likely to remain trapped along the coast.

Most particles stay within the surface mixed layer during their first month at sea, typically above about 15 m in summer and deeper in winter. As a result, neutrally buoyant and positively buoyant particles often experience similar pathways. Wave‑driven Stokes drift is relatively small compared with mean currents in this region; it slightly increases travel distance but does not substantially alter where microplastics accumulate.

Seasonal rhythm: steady on the bottom, dynamic at the surface

Seabed accumulation shows strong geographic persistence with modest seasonal modulation. Urban hotspots remain in place throughout the year, tightening when sinking is strong and spreading alongshore when it is not. River‑sourced settled microplastics remain concentrated near the Mississippi and Atchafalaya mouths under realistic sinking.

Suspended microplastics, by contrast, swing with the seasons. Along Florida’s west coast and east of the delta, alongshore bands shift longitudinally as winds and currents vary. On the Texas shelf, weaker summer currents tend to pile particles closer to major urban centers, while other seasons favor longer alongshore transport.

Protected areas: exposure is highest nearshore

Most marine protected areas (MPAs) in the northern Gulf sit in nearshore waters—the same zones where microplastics build up. Overall, river‑borne plastics dominate MPA exposure. The Texas Wildlife Refuge is particularly vulnerable: although the land unit is well shielded, its adjacent marine component is repeatedly bathed in river‑driven microplastics. The West Florida Shoreline region is more strongly influenced by urban outfalls, suggesting that local source control could pay immediate dividends. Flower Garden Banks, the only offshore MPA in the study area, is affected by both suspended and settled particles, with river sources again providing most of the input. Its position near a modeled gradient introduces some uncertainty but underscores that offshore reefs are not immune.

Who’s most at risk? Species‑level exposure

Because many Gulf species shift between pelagic and benthic habitats across their life cycle, both suspended and settled microplastics matter. River‑sourced suspended particles drive the highest exposure across all species examined. Red snapper emerges with the greatest overall stress, closely followed by the critically endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtle for suspended plastics; settled exposure is also substantial for both. Bottlenose dolphin and threadfin shad, which are fully pelagic, show elevated stress from suspended microplastics. The mussel species examined experiences a mixed signal from both rivers and urban sources.

Habitat overlap explains much of this risk. Kemp’s ridley turtle and red snapper use extensive nearshore habitat west of the Mississippi delta and across the central Texas shelf—areas repeatedly modeled as microplastic hotspots. Bottlenose dolphin habitat spans coastal and offshore zones on both sides of the northern Gulf, intersecting multiple areas of elevated concentration.

What this means for management

The model points to a few clear priorities. Cutting microplastic loads in the Mississippi–Atchafalaya watershed would reduce the dominant source of exposure across the northern Gulf. Near‑source wastewater interventions along Florida’s west coast and the Texas urban corridor could quickly shrink persistent coastal hotspots. Finally, targeted monitoring within vulnerable MPAs and critical habitats—especially along the Texas shelf and west of the delta—would help track progress and protect species most at risk.

Leave a Reply